History by Donna Strange

Pen and ink drawings by Glenn Lehew

St. John’s Episcopal Church of Antrim Parish may have been

constructed in 1844, but its origins began several centuries earlier. In May

1752, the King of England and the Governor of the Colony of Virginia established

“Antrim Parish,” an area that included Halifax, Pittsylvania, Patrick, Henry

and Franklin counties. This area was named after Antrim Parish in Northern

Ireland, one of few areas in that country where the Church of England (or

Anglican Church) prevailed. At this time in America, the Church of England had

a dominant presence in the middle colonies, especially in Virginia’s newly

settled areas. How the Episcopal Church—in the eighteenth century often called

the Protestant Episcopal Church or the Methodist Episcopal Church—developed in

Antrim Parrish and in particular Halifax County, was due largely to a dedicated

group of vestrymen determined to bring the Word of The Lord to a vastly

unsettled part of the Commonwealth.

The Early Parish

The Book of Common Prayer, first printed in 1549, provided a

framework for worship services that families could use in their homes,

especially helpful when there were no churches or churches were too far away to

travel for Sunday services. The Book of Common Prayer, still used today, serves

as a complement to the Bible and is called “common prayer” because it invites

all people to pray together.

In the early 1700s, the area we now call Halifax County was

sparely populated and had only a few established coach roads. There were no

towns or churches. Those who could read became lay readers, reading from the

Book of Common Prayer to family members and neighbors who gathered in homes. By

the time of the American Revolution, several small churches or chapels had been

built and references to them can be found in the Antrim Parish Vestry Book now

housed in the Halifax County Courthouse.

Antrim Parish vestrymen, who were well respected in their

villages, measured land boundaries and collected taxes to provide for the poor

and support a rector or minister. William Chisholm, a candidate for orders, was

in Antrim Parish in 1752, but boarded a ship for England to be consecrated by

the Bishop of London and nothing more was heard of him. The two first recorded

rectors were Rev. William Proctor, who was paid 2,000 pounds of tobacco for his

services in 1753, and Rev. James Foulis. Rev. Foulis was in the parish until

1759. In 1762, Thomas Thompson, then an old man, served a few months until Rev.

Alexander Gordon was inducted. Rev. Gordon, a Scotsman, served the area until

1775, but became disillusioned as colonists prepared to break away from English

rule, and retired to Petersburg for the remainder of his life.

By the mid-1700s, there were several parish churches. One

was St. Patrick’s, built in 1764 adjacent to Boyd’s Ferry on the south side of

the Dan River. (By 1811, St. Patrick’s Church was no longer mentioned in local

records.) St. George’s Church at Peytonsburg, erected on vestryman Joseph

Terry’s land, was completed around 1765. There was also a church built not far

from the courthouse in the Love Shop area. Parish records list Rev. Alexander

Hay as the rector from 1790 until 1818, followed by Rev. John Stark

Ravenscroft, who moved to North Carolina after several years and was elected the

first Bishop of North Carolina in 1823.

Mount Laurel Church was built circa 1820 with funds

solicited from other denominations and became a “free church” to be used by all

religious groups. A church had also been erected at Meadsville and Reverend

Charles Dresser, rector of the Love Shop area church from 1828 until 1838, gave

his last sermon there before leaving the area. These churches, like the other

early churches are no longer standing.

Rev. Dresser, before leaving to become President of Jubilee

College in Peoria, Illinois, requested vestrymen to raise money for a

“Protestant Episcopal Church” to be constructed in Halifax. (Dresser is also

known as the Episcopal minister who married Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln in

Illinois.) Among the vestrymen at the time were James Bruce, John Wimbish,

William Bailey, and William Clark. A local resident, Samuel Williams, was paid

$5.00 for land on which St. Mark’s Episcopal Church was built in 1828.

Episcopalians worshiping at St. Marks included the Bruces, Chalmers, Edmondson,

Toot, Howerton, Cabaniss, Barksdale, Craddock, Green and Wimbish families.

The Protestant Episcopal Church congregation outgrew the

modest-sized St. Mark’s in a less than three decades. Reverend John Grammar,

who served as rector from 1839 to 1858, asked vestryman Dabney Cosby, Jr., to

build a larger church and land was purchased nearby from Robert and Martha

Gilliland and John and Pamela Wilson for $600.00. In 1844 St. John’s Episcopal Church was completed.

St. John’s Episcopal Church is a classic example of Greek

Revival architecture. The pedimented gable front of the Grecian temple-like

building, features four flat pilasters supporting a massive Ionic entablature

that extends around the sides of the building. Centered between the front pilasters is a tall recessed entranceway

with two handsomely paneled doors that open into the narthex. On each side of

the church are tall stained glass windows topped with plain stone lintels.

(Church windows had triple sashes with clear panes until the latter part of the

1890s.)

The church walls are solid brick, over two feet in depth,

with the exterior covered in stucco and scored to simulate blocks of granite.

This treatment is called roughcasting, and was introduced in the area by Dabney

Cosby’s father, Dabney Cosby, Sr., who helped the younger builder during the

church construction. Cosby, Sr., a brick mason who had worked with Thomas

Jefferson on the construction of the University of Virginia. He and his son had

recently completed construction on the county courthouse and built several

large brick homes in the county.

In the

narthex identical winding stairways are located on either side of the entrance

leading to a balcony at the back of the nave (sanctuary). Originally the

balcony was horseshoe shaped and extended along the sides of the nave atop the

upper third of each window. The area was reserved for slaves who attended

church with their respective families. Under

one of the balcony stairways is a winding stair that leads to an undercroft that

features a choir robbing room and a large room supported by eight round columns

of stuccoed brick.

In the narthex, two doors, each aligned with the aisles,

lead into the nave. Inside, the church retains its original painted wooden pews

and a chancel arch that features reeded pilasters supporting an entablature

embellished with laurel wreathes and a heavy molded cornice. In the center of

the nave is an exceptionally large

plastered ceiling medallion with egg and dart trim, rosettes, and a raised Star

of David design in the center.

Those serving

on the Vestry when St. John’s was consecrated included William Bailey, Thomas

G. Coleman, James Coles Bruce, William Holt, Phillip Howerton, Charles H.

Cabaniss, Elisha Barksdale, Jr., Judge William Leigh, Thomas J. Green, John

Sims and David Chalmers. In 1852, there were 82 communicants, 65 white and 17

colored. There had been three marriages, one white and three colored, and seven

funerals, three white and four colored. By 1856, the congregation had grown to

111 communicants and in 1860, an increase of four new members were noted in the

diocesan report.

Rectory Completed

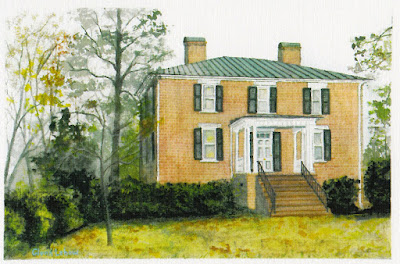

St. John’s Rectory, also built by Dabney Cosby, Jr., was

completed in 1845. It is built of brick laid in Flemish bond, but unlike the

church was not covered with a stucco or roughcast finish. Built in the classic,

symmetrical Greek Revival style, the two-story, three-bay, central passage

dwelling sits on a high English basement with porticos covering the front and

back entrances. The front and back entrance doors have transoms, and windows on

all floors are capped with stone lintels. The house has a hipped roof, two

interior chimneys, and a wide central hallway. Flanking the hallway are two

rooms on each side downstairs and upstairs. The large basement once served as

the church’s parish house and occasionally, when St. John’s furnace did not

function properly, the basement was used for church services.

The Rectory also served as a home for young boarders who

attended the Halifax Episcopal Male Academy from September 1895 to 1900. J. G.

Shackleford, who was St. John’s rector at the time, was a faculty member and

served as President of the Academy’s executive committee.

Extensive alterations took place in 1890s, when Rev.

Shackleford served as rector. Balconies along the sides of the church were

removed and the center portion of the chancel arch was extended to include an

enlarged chancel or altar area, with a semi-circular apse and three stained

glass windows. A sacristy was built on the west side of the apse and on the

east side, a rector’s vesting room. In the early 1900s, the triple sash

multi-pane windows were replaced with stained-glass windows including the three

pictorial windows in the apse area.

Various renovations have been made from time to time to

update the facilities, fixtures and furnishings. St. John's rectory was sold in the fall of 2017.

St. John’s Parish House, built in 1962 provided much needed

space for Christian Education classrooms and an office for the Rector. In 2013,

the parish house received a major renovation. The nursery was refurbished and

classrooms updated for children on the lower floor. On the first floor, on one

side of the hall, the Rector’s office was redesigned to have a sitting

area/office and boardroom with small kitchen, and the other side of the hall

was reconfigured to include two spacious offices and a chapel with stained

glass windows.

Some of the

most noticeable changes included the installation of a handicapped ramp at the

entrance and the much needed landscape renovation and tree removals in St.

John’s churchyard. Gravestones and memorials were cleaned and repositioned and

shrubbery pruned. Today, the graves of many members are easily accessable and

the pleasant surroundings encourage family members to keep graves clear of

debris. Many notable Southside Virginians are

buried at St. John’s, including John Ragland, an early vestryman and

Revolutionary War patriot. Ragland was born in 1751 was a member of Antrim

Parish for fifty years. Others buried at St. John’s include members of the

Dabney Cosby family, builders and brickmasons who built St. John’s Episcopal

Church and rectory and many homes and public buildings of note in the area. Jefferson

Davis VanBenthuysen, nephew and namesake of the President of the Confederacy is

buried at St. John’s as are many ancestors of current members.

St. John’s has a long line of faithful communicants and many nineteenth

century families such as the Holts, Easleys, Edmunds, Owens, Colemans and

Faulkners join those early parishioners and vestrymen listed previously who

have all provided leadership, monetary support and spiritual guidance. Men who

were childhood members of the church and later became priests include four

Kinsolving sons (two of whom became bishops). Charles Clifton Penick became a

missionary bishop to Liberia and George Purnell Gunn became Bishop of the

Diocese of Southern Virginia. Two Ribble sons became ministers and Robert Soper

was also ordained a priest.